Which of Marx’s Social Republics would you choose?

Gil S critiques Leipold’s Citizen Marx, arguing it does not take Marx’s republican goals seriously enough

Gil Schaeffer

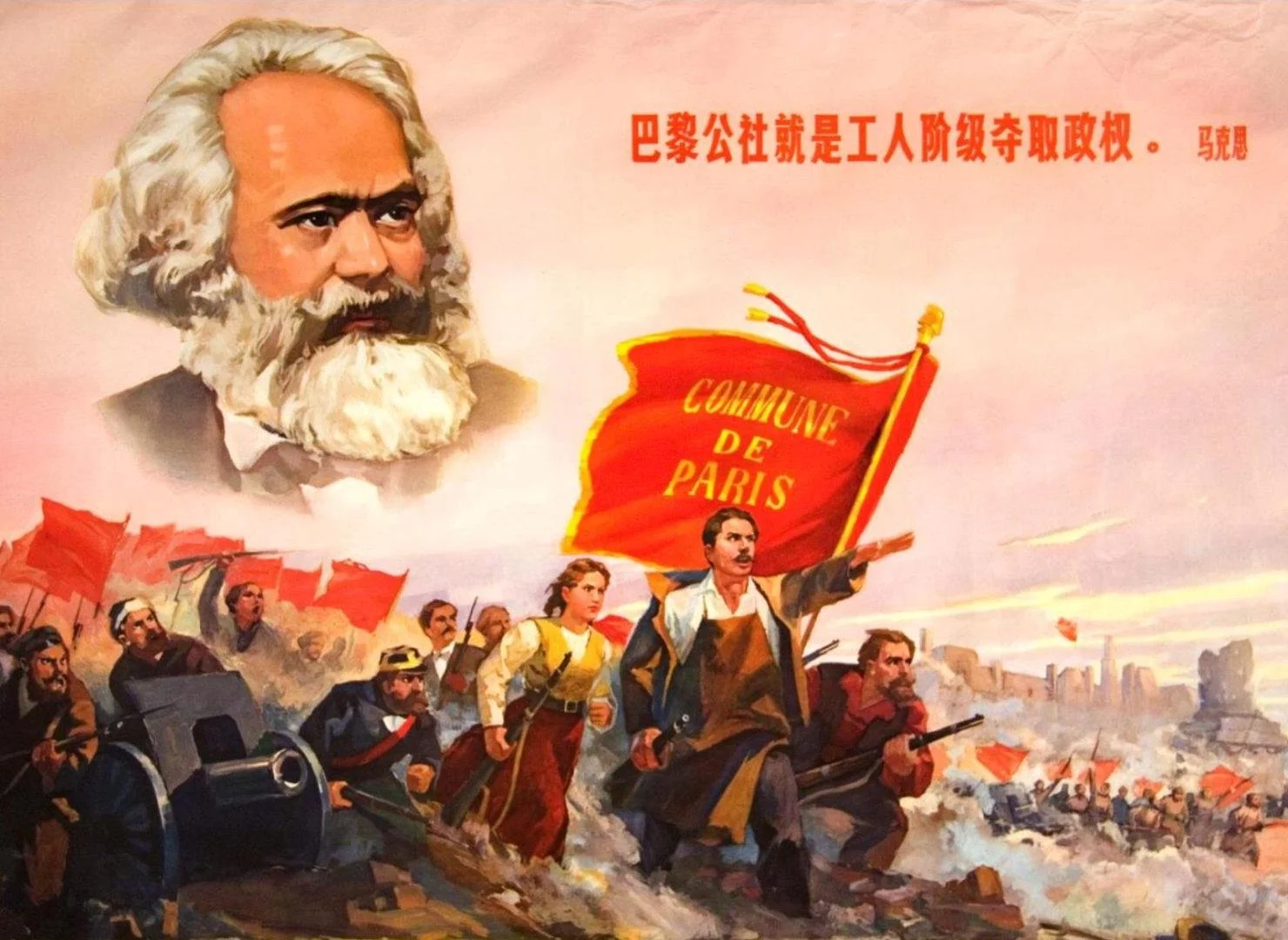

There is no longer any doubt that Marx’s conception of socialism was democratic republican through and through. Hal Draper and Richard N. Hunt made this claim in the 1960s and 1970s, and Bruno Leipold builds on and further substantiates their original insights in Citizen Marx. So this review will not be directed at those holdouts on the left who refuse to acknowledge these historical findings. Mike Macnair’s review of Citizen Marx in Jacobin took care of that. My focus will be on the three different versions of a social republic that Marx constructed at different points in his political career and the implications of each for us today.

MUG members have been studying and discussing Bruno Leipold’s writings for a number of years. His 2020 essay, “Marx's Social Republic,” is in the MUG Reader, and Citizen Marx has been a subject of debate on the MUG Discord since it was published late last year. But for those not already familiar with Leipold’s writings, it is necessary to understand from the start that the “social” in Leipold’s “Marx’s Social Republic” does not refer to socialism or to some set of social policies that must be implemented for a republic to qualify as a “social republic.” That is what Marx meant by a “social republic” in The Class Struggles in France (1850), but that is not what the “social” in “social republic” stands for in The Civil War in France (1871) or in Citizen Marx. As Leipold explains:

Much of The Civil War in France is taken up with a moving defense of the Commune’s actions and corresponding condemnation of the atrocities committed by the Versailles government. But its theoretical appeal comes from its third section, where Marx gave a glowing endorsement of the Commune’s political institutions and identified them as the appropriate political form to bring about a socialist society. In one of many statements of this core idea, Marx argued that ‘the Communal Constitution would . . . serve as a lever for uprooting the economical foundations upon which rests the existence of classes, and therefore of class rule.’ It was this political breakthrough that Marx thought was the signal contribution of the Commune rather than any of its social reforms. He maintained that ‘The great social measure of the commune was its own working existence’ and what few ‘special measures’ it had introduced (such as the abolition of night work and workplace fines) flowed precisely from it being ‘a government of the people by the people.’ Or, as he otherwise summarized it, ‘the actual “social” character of their Republic consists only in this, that workmen govern the Paris Commune!’....(pp. 355-6)

For Marx, the social republic of the Commune was ‘social’ not because it was a socialist economy but because it had the right political and constitutional features to reach it…. (p.356)

Leipold continues:

This represents an important shift from Marx’s usage of ‘social republic’ in his 1848 writings. To return to the three aspects of a republic we outlined in Chapter 4 [p. 221], Marx there understood a ‘social republic’ to mean either (i) workers forming the governing class in a republic or (ii) that the economy of the republic was a socialist one. There was no sense in his 1848 writings that a social republic referred to (iii) a republic with a constitution that was particularly suited to maintaining or bringing about those first two aspects. By comparison, in his 1871 writings on the Commune, Marx explicitly dropped the economic meaning he attached to a social republic, while continuing to use it to refer to the working class being the governing class….(356-7)

Leipold’s comments are accurate in three important ways, but seriously misleading in another. First, it is true that Marx thought the Commune was “social” because of its constitutional structure and working-class governing composition, even though it did not implement major economic and social reforms, much less socialism. Second, Marx’s use of the word “social” to apply to constitutional structure rather than economic and social policies was a change from [most] of his writings on the 1848 French Revolution. Third, the addition of the category of constitutional structure in his writings on the Commune means Marx began to analyze the nature of republics from three different angles: constitutional structure, governing class composition, and the content of social policy, rather than from just the two angles of governing class composition and social policy. The misleading part is that Marx did in fact discuss the “social” character of democratic constitutions in his writings on the 1848 French and German Revolutions and the Chartists, but Leipold considers these earlier constitutional discussions “bourgeois” in contrast to the genuine working-class character of the Communal Constitution. Why?

Marx and Engels on the Working-Class Character of Universal Suffrage, 1846-52

Leipold’s review of Marx’s and Engels’ writings on universal suffrage begins with Chartism (pp. 245-6):

In addition to civic freedoms, the other key political institution of the bourgeois republic that Marx saw as a critical weapon in the struggle for communism was manhood suffrage (which he refers to as ‘universal’ suffrage). Though universal (manhood) suffrage might initially lead to the rule of the bourgeoisie (as it had in the Second [French] Republic), Marx was confident that its introduction would eventually lead to the working class coming to political power, especially once it had become the majority of the population and properly organized itself. That was particularly pronounced in his and Engels’s lavish praise of Chartism. We saw in chapter 3 [p. 170] that in 1846 they had already aligned themselves with its goal of ‘a democratic reconstruction of the Constitution upon the basis of the People’s Charter,’ by which the working class ‘will become the ruling class of England’...That enthusiasm continued once they were both exiled to Britain [after the 1848 revolutions]. Marx argued that since ‘the proletariat forms the large majority of the population . . . Universal Suffrage is the equivalent for political power for the working class of England.’ Marx is so sure of this consequence that he asserts that universal suffrage’s ‘inevitable result here is the political supremacy of the working class.’ He places such importance on this political goal that he even holds that achieving universal suffrage would ‘be a far more socialistic measure than anything which has been honoured with that name on the Continent.’ Engels similarly proclaimed that the English working class had no ‘guarantee for bettering their social position unless by Universal Suffrage, which would enable them to seat a Majority of Working Men in the House of Commons.’

Leipold immediately follows with a catalogue of Marx and Engels’ similar comments on the importance of universal suffrage in France (pp. 246-7):

Marx and Engels’s confidence in universal (manhood) suffrage similarly extended to France (though its less advanced class composition meant they thought that universal suffrage would initially bring a broader popular coalition of proletarians, peasants, and petty bourgeoisie to power). Particularly emblematic for them were the important by-elections of 10 March 1850, in which left-wing Montagnard candidates won several important victories despite repressive measures against them. Marx and Engels saw the elections as a prime example of how universal (manhood) suffrage would necessarily lead to a continual expansion of political power for the left….

The 10 March elections were indeed a severe political shock to the party of order, who concluded that the Second Republic’s brief experiment with universal (manhood) suffrage was too dangerous to continue. They introduced a number of technical measures on 31 May 1850 that effectively excluded much of the working class and limited the franchise to two-thirds of its previous size. Marx saw in this further confirmation of the threat universal (manhood) suffrage posed to the bourgeoisie, commenting that on ‘March 10 universal suffrage declared itself directly against the rule of the bourgeoisie; the bourgeoisie answered by outlawing universal suffrage.’ The experience had shown that though ‘[b]ourgeois rule is the outcome and result of universal suffrage, . . . is the meaning of the bourgeois constitution,’ their democratic commitment crumbles the ‘moment that the content of this suffrage, of this sovereign will, is no longer bourgeois rule.’

and then Germany (p. 247):

For Marx, the bourgeoisie’s retreat from universal (manhood) suffrage captured the central tension of the bourgeois republic—that it tried to reconcile political equality with social inequality, i.e., representative democracy in the political sphere and capitalism in the economic. In a striking and under-appreciated passage in Die Klassenkämpfe in Frankreich, he argued that,

The fundamental contradiction of this constitution [the bourgeois republic], however, consists in the following: the classes whose social slavery the constitution is to perpetuate, proletariat, peasantry, petty bourgeoisie, it puts in possession of the political power through universal suffrage. And from the class whose old social power it sanctions, the bourgeoisie, it withdraws the political guarantees of this power. It forces the political rule of the bourgeoisie into democratic conditions, which at every moment help the hostile classes to victory and jeopardize the very foundations of bourgeois society….

Why Does Leipold Believe Universal Suffrage is Bourgeois?

Marx’s characterization of the Charter as “socialistic,” even though its demands were purely political, seems similar to his characterization of the Communal Constitution as “social.” But Leipold sees a fundamental difference between the two. In an extended discussion (pp. 241-50), Leipold explains why Marx’s confidence in the Chartist version of a democratic republic was “too optimistic”:

Marx’s account of the ideological and political advantages to the working class of the bourgeois republic’s civic freedoms and democratic suffrage is an important counter to some of the tired antidemocratic stereotypes of Marx’s thought. Marx was evidently supportive of their introduction and very optimistic about their eventual consequences. The irony is that Marx may in fact have been too optimistic. More extensive experience with bourgeois republics than Marx had access to produces a less encouraging picture. On the ideological front, Marx certainly makes a plausible case that a republic would sweep away some of the ideological protection provided by a monarchy. But he also underestimates the degree to which bourgeois republics could and would develop their own ideological safeguards. The removal of formal political and legal inequalities might help focus struggle on continuing social inequalities, but it can also make those social inequalities appear to be the result of individual talent and effort. Generations of twentieth-century Marxists have, of course, traced the myriad ways in which ideological legitimation and pacification in bourgeois republics is maintained through the cultural sphere. Moreover, the political structures of a republic can themselves provide a useful ideological shield, particularly the status that comes from being a regime elected by the people. (p. 248)

In the above passage, Leipold is no longer discussing what Marx thought representative democracy would produce, but what Leipold thinks it has produced—a “bourgeois republic” that combines a constitutional representative democracy with the continuing rule of the bourgeoisie. This disappointing result leads Leipold to conclude:

In Marx’s eagerness to distinguish himself from the various antipolitical socialisms, he overlooked some of the more radical insights on representation and political participation from his own early republicanism. In taking much of the political structure of the bourgeois republic as given and advocating for the working class to take power within its strictures, Marx might also be seen to have insufficiently developed a key aspect of his own 1848 constitutional analysis—that the bourgeois republic was constitutionally set up to ensure bourgeois rule. That insight might have led to the conclusion that if the working class was to emancipate itself socially, it would require its own republic, with a more radically democratic constitution. (p. 250)

That “more radically democratic constitution” was the Commune, which in Marx’s account included the democratic election of representatives, like the Charter, but went further and specified that representatives should be bound by specific instructions from the electorate, subject to recall, and serve short terms. Marx also specified that the legislature should carry out the executive functions of the state; members should be paid workmen’s wages; and all judges, administrators, militia, and police officials should also be elected and subject to recall. In Leipold’s view, Marx’s writings on the Commune, after two decades dedicated to the problems of “bourgeois republics,” marked a return to his earlier (1843) theory of "True Democracy,” a concept that combined modern representative electoral democracy with elements of direct democracy drawn from Rousseau and the Athenian polis. (pp. 109-18)

Two Flaws in Leipold’s Analysis

I have two major disagreements with Leipold’s analysis:

The Commune in reality never functioned according to the ideal that Marx constructed in The Civil War in France. Leipold recognizes that Marx exaggerated the Commune’s accomplishments but retains Marx’s ideal of the Commune as a model for current politics because he believes the version of democratic republicanism represented by the Chartists has been achieved but has failed; and

We can only assume Leipold believes the United States is one of those representative democracies because he says nothing to the contrary. Using the three dimensions for analyzing republics outlined above, it seems Leipold thinks the US has a democratic constitutional structure combined with a bourgeois governing class overseeing bourgeois social policies. But the US has never had a democratic constitution. For that reason, the traditional Chartist goal of universal and equal suffrage in elections to a single legislature is still relevant in the US and should not be denigrated as a bourgeois stricture. (Though we have learned since the Chartists that proportional representation in multi-member districts is a much better system than Britain’s single-member districts.)

Here is what Leipold has to say about Marx’s exaggerations:

Marx’s account of these political institutions—supposedly based on the Commune—did not always correspond to what the Commune had in fact implemented. The discrepancy might partly be explained by his imperfect access to information from Paris. But the more pertinent explanation lies in that Marx was not trying to provide ‘an account of what the Commune was, but of what it might have become.’ With The Civil War in France, Marx was making a political intervention into how the Commune should be interpreted. With anarchists, Blanquists, radical republicans, and even Comtean Positivists vying to appropriate the Commune, Marx wanted to stamp his own account on what it implied for radical politics. That meant highlighting those aspects that he endorsed and seizing on tendencies that he believed should be developed in future revolutionary iterations. (pp. 361-2)

One example of Marx’s exaggeration is the claim that the Commune paid its officials only “workmen’s wages”:

The Commune had in fact only limited the salaries of public officials to a maximum of 6,000 francs a year when workers (in 1871) earned about 5 francs a day, giving them roughly 1,500 a year. Marx was aware of the actual figures, so his bending of the facts was a deliberate exaggeration of what the Commune had in fact achieved (an already radical step), in the direction of what he hoped future communist regimes would do. (pp. 382-3).

Another example is Marx’s omission of the Commune’s provision that officials might be appointed after competitive examinations rather than only by election:

Marx’s repeated call for all public officials to be ‘elective, responsible, and revocable’ can be seen as a pithy formulation of this demand. But Marx’s account also subtly departs (perhaps deliberately so) from the Commune’s declaration by omitting its specification that public officials might be appointed ‘by election or competitive examination.’ (p. 381)

Marx himself gave a considerably more modest assessment of the Commune’s accomplishments ten years later, a period during which he continued to support the demand for universal and equal suffrage:

[A]part from the fact that this was merely the rising of a town under exceptional conditions, the majority of the Commune was in no sense socialist, nor could it be. With a small amount of sound common sense, however, they could have reached a compromise with Versailles useful to the whole mass of the people -- the only thing that could be reached at the time. The appropriation of the Bank of France alone would have been enough to dissolve all the pretensions of the Versailles people in terror, etc., etc. (Marx to Domela Nieuwenhuis, 2/22/1881)

The Commune survived for only two months while under siege by a much more powerful military force. Everyone must draw their own conclusions about the Commune’s actual accomplishments and how successful its vision of democracy would have been had it survived and then been integrated into a larger republic encompassing all of France. My judgment is that the Commune has been over-romanticized, not least by Marx himself, and any realistic present-day attempt to implement Marx’s proposals for deprofessionalization and citizen participation depends on first winning the battle for universal and equal suffrage.

Next to Last Words

For the reasons given above, Citizen Marx is not a politically useful book for us in the United States. It takes no notice of the undemocratic structure of our constitutional system and dismisses universal and equal suffrage as a bourgeois ploy designed for ideological pacification.

Leipold’s historical accounts of the French and German Revolutions of 1848 are interesting and informative, but Citizen Marx is not a comprehensive chronological narrative like Richard N. Hunt’s The Political Ideas of Marx and Engels. The history in Citizen Marx is selective and deployed mainly as a vehicle to illustrate Leipold’s particular conception of political theory, which is derived from an academic circle formed around the study of Machiavelli’s republicanism. This strand of republicanism is elitist in its origins and differs from the equal liberty form of democratic republicanism created by the Levellers during the English Civil War. It has little or nothing to offer to our democratic socialist movement, but for those curious about what is currently going on in this academic arena, a few additional comments follow.

Leipold’s Republican Theory

Leipold’s conception of republicanism is derived from the “foundational works [of J. G. A. Pocock, Philip Pettit, and Quentin Skinner] that unearthed the buried history of the tradition [in Machiavelli and English ‘commonwealthmen’ like Harrington and Sydney] and established it as the thriving field of study that exists today.” (quote, p. 17; citation of foundational works and the buried tradition, fn 58, p. 17) This is an odd intellectual project to draw from because these authors, although they criticize the Lockean liberal/market notion of “freedom as noninterference,” share with market liberals a suspicion of what Pettit calls “populist democracy” and generally agree with traditional constitutional separation-of-power arguments favoring safeguards against an excess of democracy. And, to the best of my knowledge, all of these authors classify the US as a democracy.

It’s not as if a general theory of freedom as nondomination is wrong, but that general theory needs to be concretized by commitments to specific political goals and institutional forms. Pettit et al. generally think modern liberal “democracies” just need nudges and reforms. Leipold is for nondomination in the ideal form of the Paris Commune and thinks universal suffrage is bourgeois. I’m for the Leveller-Paine-Rights of Man-Chartist-US Radical Republican theory of nondomination that focuses on first establishing universal and equal suffrage as the precondition for the longer-term aim of maximizing the spread of democracy into all other political, social, and economic institutions. Engels invokes this third republican tradition in the following passage. It was the strongest influence on Marx and Engels’s political thinking and the tradition we should continue today:

In October 1846, while disseminating his own tactical ideas among the German artisans in Paris, Engels defined the proper road to communism as a ‘forcible democratic revolution.’ A month later, in an article chastising the French democrat Alphonse de Lamartine for proposing indirect elections, Engels appealed to the legendary Constitution of 1793: ‘The principles, indeed, of social and political regeneration have been found fifty years ago. Universal suffrage, direct election, paid representation— these are the essential conditions of political sovereignty. Equality, liberty, fraternity— these are the principles which ought to rule in all social institutions.’ (Hunt, The Political Ideas of Marx and Engels, vol. 1, p. 136)

Are the Chains of Capitalist Economic Domination Visible or Invisible?

Leipold also has a chapter on economic domination titled “Chains and Invisible Threads,” which reviews Marx’s writings on wage slavery. But there is an anomaly in Leipold’s account and Marx’s theory that Leipold does not clarify. It involves the fact that wage workers themselves and other social observers understood the nature of wage slavery years before Marx and Engels entered politics. Leipold cites E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class and quotes from the writings of Felicite de Lamennais as evidence for the existence of this common understanding:

Lamennais in his hugely popular 1839 pamphlet De l'esclavage Moderne (On Modern Slavery)...argued that their reliance on wages to survive… meant that between ‘the capitalist and the proletarian, therefore, almost the same actual relations exist as between the master and the slave in ancient societies.’ Though proletarians enjoyed the freedom to sell their labor, which Lamennais considered ‘an immense advantage over the ancient slave,’ the proletarian’s dependency on a capitalist meant that ‘this freedom is only fictitious.’ (pp. 29-30)

Of course, Marx took up the concept of wage slavery and subjected it to minute analysis in Capital, but the anomaly is that Marx characterized these wage relations as “invisible”:

‘The Roman slave was held by chains; the wage-laborer is bound to his owner by invisible threads.’ (Citizen Marx, p. 15, 304, 315).

Leipold chooses Marx’s characterization of invisible threads as the title of his chapter, even though he cites other evidence in the same chapter that the constraints of the wage-labor relationship were apparent to many workers and other social observers. How did an understanding of wage slavery that was once commonplace become invisible? Did it actually become invisible, or was Marx exaggerating? Or perhaps his argument was aimed instead at a particular part of the working class that was not as politically advanced as those workers who could see capitalism’s chains?

Partial answers to these questions are that Marx did exaggerate for dramatic and political effect (whether he was aware of it or not), and his argument was in part aimed at English trade unionists and French Proudhonists in the First International who proposed inadequate solutions for wage slavery. But the fact is, there were always advanced parts of the working class who were never duped by capitalist notions of freedom and continued to believe in the necessity of democracy and socialism. It was these advanced workers and their representatives who created the Commune and the later Marxist political parties.

The belief that something invisible in the wage labor relationship was uncovered by Marx is questionable and is generally associated today with the further belief that capitalists maintain their rule by ideological mystification of the working class through cultural mechanisms, a belief Leipold also holds. Such beliefs and theories, in my opinion, are part of a larger “dominant ideology thesis” that shifts the main responsibility for the weakness and disorganization of the US left from intellectuals who fail to see the political importance of our undemocratic political system onto a working class supposedly blind to its own enslavement.

Universal and Equal Suffrage Is Not Part of the Old State Machinery

The Civil War in France is famous for Marx's declaration that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes;” and Leipold repeats it several times in Citizen Marx. Marx and Engels reemphasized this point in their 1872 Preface to a new edition of the Manifesto, saying they would now want to change the text of a revised Manifesto if it had not already become a historical document which they no longer had any right to alter. These remarks have been taken by many, including Leipold, to be a self-criticism by Marx and Engels of their own previously held views on the state and revolutionary strategy. Here are Leipold’s comments:

Marx himself recognized that this insight—that the state needed to be fundamentally transformed—represented a shift in his own thinking. When the Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei was republished in 1872, Marx and Engels made sure that this insight was reflected in a new preface:

In view of the practical experience gained, first in the February Revolution, and then, even more so, in the Paris Commune, where the proletariat for the first time held political power for two whole months, this program has in places become antiquated. Particularly, the Commune delivered the proof that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made State machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.”

Marx and Engels’s public admission that they had been mistaken in their earlier political program is a rare example of explicit self-criticism and self-correction (especially in the case of Marx, who was not usually given to such reflective displays). Marx clearly thought the Commune was a historical breakthrough important enough for him to publicly revise his views. (pp. 358-9)

This interpretation is wrong.

The strongest evidence that Marx’s views on the state had not changed is his April 1871 Letter to Kugelman, where he recalled his statement in The Eighteenth Brumaire (1852) that “the next attempt of the French revolution will be no longer, as before, to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another, but to smash it.” If Marx had always believed the bureaucratic-military machine had to be smashed, who did not? In The Civil War in France, Marx identifies the bourgeois revolutions of 1830 and 1848 as instances of the transfer of the machine rather than its destruction. Marx was only referring to previous bourgeois revolutions, not working-class revolutions, because there hadn’t been any. Only the Commune, the first working-class republic, was able to destroy it for a short time. But within the Commune itself, there were elements who, prior to the establishment of the Commune, did advocate seizing the old state machinery and using it. Marx only alludes to these elements obliquely in The Civil War in France, but Engels explains in his 1891 Introduction that

The members of the Commune were divided into a majority of the Blanquists, who had also been predominant in the Central Committee of the National Guard…. The great majority of the Blanquists at that time were socialist only by revolutionary and proletarian instinct…And did the opposite of what the doctrines of their school prescribed [which was to seize centralized state power themselves and impose a temporary dictatorship of an elite few].

Marx and Engels’s criticism was aimed at the Blanquists, not themselves.

Leipold’s particular twist on the “Marx and Engels were criticizing themselves” interpretation involves defining universal and equal suffrage retrospectively as bourgeois, a position never held by Marx and Engels themselves after the mid-1840s. Leipold rejects the Chartist universal and equal suffrage model of the social republic and focuses instead on the largely unrealized Communal ideal of imperative mandates, elections of officials, and recall, even though the latter are impossible without the former.

We in the US have to choose which parts of Marx's writings on democracy we should emphasize: his and Engels's lifelong advocacy of universal and equal representation in a single legislative body or his more speculative projections of what he hoped maximum citizen participation might look like in the future after the battle for democracy had been won. Leipold focuses on the speculative projections, apparently because he thinks universal and equal suffrage already exists. I disagree. Winning universal and equal suffrage is still our first priority.