Socialism in One City? Sewer Socialism in Context

Comrade Steven critiques Eric Blanc’s history of Sewer Socialism

Steven R

Zohran Mamdani’s election is easily the most significant electoral accomplishment of the organized US socialist movement in over a century. The prospect of a cadre member of DSA governing the beating heart of American capitalism under Donald Trump’s presidency opens a range of new strategic questions. How should DSA’s internal democracy relate to the municipal administration of a city of eight million? How do we balance the needs of the national movement with the needs of NYC-DSA as it fights to enforce Zohran’s agenda? What do we do about the police now that one of ours is their boss?

These considerations would have been incomprehensible to the US Left of a decade ago. It is only natural, then, that we turn our attention to the last time socialists had to confront questions like these—the height of the old Socialist Party of America (SPA).

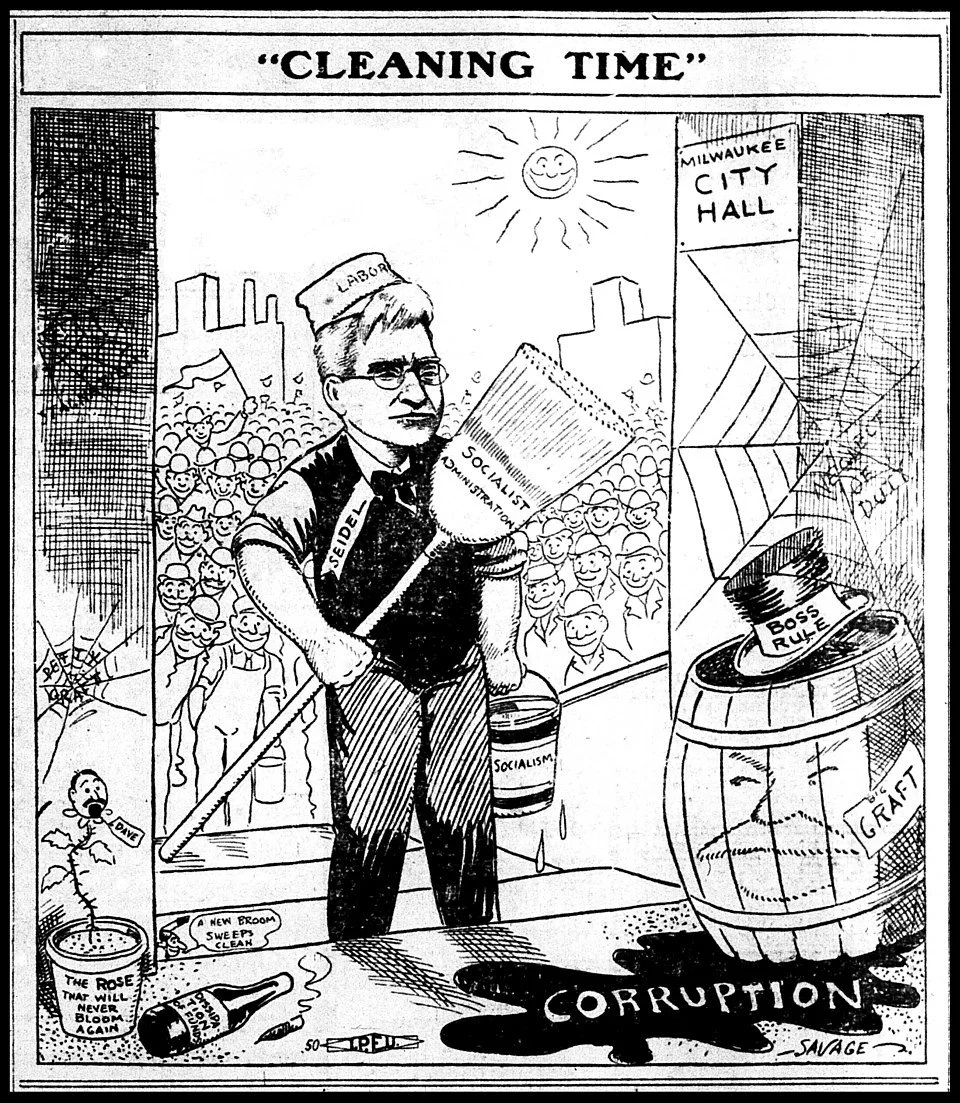

In “Socialists in City Hall? A New Look at Sewer Socialism in Wisconsin,” Eric Blanc dives into the history of the Wisconsin Social-Democratic Party (WSDP), a state branch of the SPA. The WSDP sent Socialist Victor Berger to Congress, became a powerbroker in the Wisconsin state government, and held municipal power in Milwaukee from 1910-1912 and 1916-1940. Blanc makes the case that the WSPD’s strategy of mass base-building through pragmatic, incremental reform succeeded where the national Socialist Party failed. In this just-so narrative, Wisconsin oriented to the “broad mass of working people” while the Party at large succumbed to self-marginalizing sectarianism.

The relevance of this argument is clear in the context of a Mamdani mayoralty. While Zohran has signaled that his administration will make the kind of pragmatic compromises Blanc endorses—for example, reaching far beyond the socialist bench to staff top posts in his government, going as far right as NYPD Commissioner Jessica Tisch—NYC-DSA has moved to discourage its membership from holding the new mayoralty to strict standards in favor of a single-minded pursuit of the “Affordability Agenda.” Blanc seconds this approach, arguing that socialists should disregard a more uncompromising assault on the establishment, and instead focus on gradually raising the public’s confidence in socialism by proving that we can be competent administrators who deliver increases in the standard of living.

In contrast, DSA’s more left-wing national leadership attempted to set terms on its relationship with NYC’s Alexandria Occasio-Cortez in 2024, and this year’s National Convention endorsed steps toward increased party-like discipline. Now, in the Zohran moment, NYC-DSA has taken steps to distance itself from national DSA, declining to seek a national endorsement for Mamdani and recently stirring controversy with a “local-only membership” scheme. It appears that NYC-DSA and the wider socialist movement are on two different tracks. Socialists will need to confront this contradiction as Mamdani enters office in the coming year.

In service of his argument, Blanc commits what amounts to historical malpractice with what he says—and doesn’t say—about twentieth-century American socialism. He isolates the Wisconsin sewer socialist project from its wider historical context and obscures details that fail to fit his narrative. Because of the stakes of the subject at hand, we need to set the record straight.

Milwaukee and the Mass Party

For Blanc, the WSDP took a “mass” approach and succeeded at building Socialist hegemony within Milwaukee, as opposed to the uncompromising and self-marginalizing national SPA. To construct this narrative, he blurs together two periods: the 1900s-1910s, when the SPA was the hegemonic force on the American Left and increasingly influential in wider society, and the 1920s-1930s, when it was an increasingly marginal faction of both. To be clear, it was during the earlier period that the national party was generally to the left of the sewer socialists. The later years of marginalization which killed the national SPA happened under the political leadership of the kind of "pragmatists" Blanc would point to as models to emulate. This same leadership was often part of the Wisconsin sewer socialist machine itself, or actively emulating it in places like Reading, Pennsylvania.

It was during the national SPA’s most militant period that it grew into something like a mass socialist party, the only one of its kind in American history. At a time when the party openly condemned the Constitution, welcomed insurgent industrial unionists in its ranks, and rejected compromises with the burgeoning liberal “Progressive” movement, it boasted over 125,000 members (1) and perhaps two million total active supporters(2). It won the support of between thirty and forty percent of delegates against Samuel Gompers’ establishment at the American Federation of Labor’s annual conventions (3), and was a decisive political force in major proto-industrial unions like the ILGWU and UMWA (4).

To put this in perspective, socialists today can imagine a DSA with half a million members in good standing and broad support for our political program in large, strategically situated unions like the Teamsters and the American Federation of Teachers.

More than anything the left-wing Socialists did, it was the “pragmatic” decisions to rid the party of its industrial radicals in 1913, force a split in 1919 to prevent pro-Bolshevik Socialists from taking leadership, and liquidate into Bob LaFollette’s nebulous liberal-labor coalition in 1924 that led to stagnation, disorganization, and then a long decline into irrelevancy from which the SPA never recovered. Especially after 1919, the Berger-Hillquit wing of the party had a virtually free hand in deciding its political direction, and the results speak for themselves. By the time Trotskyist entryists arrived on the scene in the 1930s, the Socialist Party was already a dead letter.

American Socialism, Right, Left and Center

Because Blanc ignores the wider context the WSDP was situated in, he can claim that no departure from the project of revolutionary socialism was needed for socialists to step into municipal administration. But we must view sewer socialism in the context of contemporary debates in the global socialist movement over Millerand's "ministerial socialism" in France and Bernstein's "revisionism" in Germany; in this light it is clearly part of the wider turn by a section of the Second International towards loyalty to the capitalist state and gradual reform as guarantors of social peace.

The sewer socialists themselves saw their project in these terms. Berger described his socialism as necessary to prevent a "fearful retribution" against the capitalist class that would "throw humanity back into semi-barbarism." (5) To prevent the catastrophe of revolution, land and industry had to pass into public ownership, but only—as Berger argued strenuously against the rest of his party—legally and with fair compensation to the capitalist class (6).

Like Bernstein, Berger and the Wisconsinites believed that the extension of suffrage to wide sections of the working class made revolution obsolete. They explicitly cast themselves in the tradition of “moderate” reformers like Henry Clay, with his compromising attitude towards the slaveowning class and gradual, compensated plan to abolish slavery, in contrast to the revolutionary abolitionists that most of the SPA revered (7). Berger saw the abolitionists and their modern equivalents, the radicals they shared a party with, as “fanatics” who posed as much a threat to the peaceful evolution of society as did the forces of reaction (8).

The WSDP's conservative socialism was already far to the right of the politics that would later bring the working class to power across the Russian Empire, and to the brink of power across Europe, in 1917-21. And it was pushed even further right by the pressures of maintaining a stable municipal administration in Milwaukee. Berger, Sleidel, Hoan and the other sewer socialists sought a party and a program that was as broadly appealing as possible to remain competitive against the united Republican and Democratic opposition.

In practical terms, this meant reducing the movement's horizons to hard-nosed municipal reform and good governance, keeping the lofty aims of political and social emancipation confined to the pages of the socialist press. It also meant making socialism “safe.” While Berger, to his credit, faced down prison to defy Woodrow Wilson’s war agenda in World War I, the actual Socialist administration in Milwaukee threaded the needle between antiwar sentiment, social patriotism, and fear of repression. It emerged on the other side supporting the imperialist war effort (9).

Another consequence was to incentivize the Wisconsin Social-Democrats to appeal to the lowest-common-denominator instincts of the workers whose votes they depended on, including racism. Victor Berger promoted the idea that “the negroes and mulattoes [sic] constitute a lower race—that the Caucasian and indeed even the Mongolian have the start on them in civilization by many thousand years.” The local party press played into lynch-mob hysteria by publishing Berger’s defense of racial segregation on the grounds that “free contact” between the races resulted in “many cases of rape” (10). In a 1907 article, republished at least as late as 1912, he declared the “brilliant culture of [the] country” was “by right an inheritance of the white race” (11).

This tendency to appeal to white workers as white workers was so bad that by 1922—a year after the infamous Tulsa Race Massacre—the Wisconsin SDP had cultivated a significant overlap in membership with the Ku Klux Klan. They ran John Kleist, a dual-carder who publicly bragged about his Klan membership, for state office (12). Amidst a nationwide awakening of Black radical consciousness, the scandal this incident provoked forced the Wisconsin socialists to take a firmer stance against the Klan and begin purging themselves of the white supremacy they had allowed to fester in the party. Kleist was not formally expelled until 1924.

“Pragmatic Marxism” indeed. Would challenging the racial attitudes of white workers in the early twentieth century have been “jumping too far ahead” of the working class? With immigration, policing, and Zionism front of mind in Mamdani’s New York, the implications of replicating a strategy that inadvertently welcomed the vanguard of contemporary American fascism into the ranks of the WSDP need stern interrogation.

Socialism and Labor

Part of Blanc’s argument rests on the claim that the WSDP was deeply rooted in the labor movement while the tactically rigid, “far left socialists” elsewhere in the SPA had “weaker roots in the class.” To illustrate the difference, he points to the Milwaukee Socialists’ successful effort to win over existing trade unions, in contrast with efforts to organize new militant unions like the Industrial Workers of the World or the Socialist Labor Party’s much smaller Socialist Trades and Labor Alliance.

Blanc is correct that “boring from within” existing trade unions was strategically valuable, but he is wrong to imply that this approach was the sole domain of the “pragmatic” right wing of the SPA. Party centrists and leftists like Eugene Debs also embraced working to transform existing unions (13). He is also right in noting that this strategy paid off spectacularly in Milwaukee. But in order to bend contemporary labor debates to fit his larger argument about "mass"-oriented pragmatism, he does a disservice to the historic struggle for industrial unionism and obscures the truth about where the lines of class unity and class division lay in the early twentieth-century labor movement.

The IWW’s “dual-unionism” should not be lumped in with the SLPs “red unionism,” nor can it be reduced to a self-marginalizing sectarian strategy. As many as one million workers may have passed through the IWW's ranks in the first fifteen years or so of its existence, drawn from among the masses of workers the dominant trade unions generally refused to organize. Some of these became important actors in the birth of the Congress of Industrial Organizations a generation later (14).

The real labor sectarians in this period were the craft-unionists who excluded the majority of American workers who were unskilled, itinerant, Black, recent immigrants, or some combination of the four. Blanc correctly identifies that boring-from-within as practiced by the WSPD was one way to break down these sectarian walls, but goes too far in insisting with (ironically) sect-like tactical stubbornness that it was the only way. Given the era’s low union density (around half of what it is today), there is no reason to believe that the two strategies could not have productively coexisted in some form (15). Later socialists like the League of Revolutionary Black Workers even experimented with such an "inside-outside" labor strategy in their own context (16).

Carrying the Socialist Flame

In explaining sewer socialism's demise, Blanc admits that it failed to build a popular base for socialism that was durable enough to survive such inevitable constraints as "employer opposition," "public opinion," and "media scaremongering" during periods of conservative backlash. Chalking up the decline and defeat of a supposedly wildly successful strategy to structural forces outside our control paints a bleak picture: it might be impossible to build a militant socialist party in the long run. The best we can hope for is to use our fleeting time in the sun to struggle for better institutions like the Milwaukee socialists did by "[pioneering] the New Deal."

Society will always oscillate between periods of radicalism and conservatism, upsurge and sedation, political plasticity and rigidity. But socialists' ability to carry the flame through periods where unfavorable conditions reign is a contingent thing.

It is likely the Socialist Party would have shrunk during the repressive and economically stable 1920s in any scenario, but its complete implosion was not inevitable. Absent the rightist coup of 1919 and the rump party's liquidation into progressivism in the early 1920s, it may have been the open and democratic SPA that seized the crisis of the 1930s to catapult socialism back into the mainstream, not the CPUSA with its militarized bureaucracy and self-destructive subservience to the twists and turns of Comintern policy. In turn, without the misadventures of the late Popular Front, the Communists and the left wing of the CIO may have been able to survive the repression of the early Cold War intact, which could have drastically altered the fate of the social movements of the 1950s-1970s.

Marxism’s historical contribution was to inject a rigorous scientific analysis of structural forces into the movement for political and social freedom we now call socialism. But what allowed it to grip the hearts and minds of millions is that it has always affirmed our power to overcome the structural obstacles facing us through collective action and make our own history out of the conditions we inherit. Obstacles like "media scaremongering" and "employer opposition" can be out-organized, though that is, of course, easier said than done. And Zohran's triumph in the shadow of Trumpism and capitalist-driven crime hysteria proves we can positively transform public opinion even in an atmosphere of reaction. This isn’t just a question of making our program broadly appealing, but of taking heroic public stands on issues like Palestine and immigration.

This kind of political courage, the courage it took for Eugene Debs and many other Socialists to go to prison or worse for opposing their government’s war aims, the courage it will take for Zohran Mamdani to follow through on promises like arresting Benjamin Netanyahu in the face of massive retaliation, is the kind of courage we in DSA should expect from our elected representatives. It is the kind of courage we must show workers they can expect from socialist politicians if we are going to reignite in masses of working people the fire that fueled Reconstruction, the SPA, and the CIO. And it is the kind of courage that requires a nationwide mass party and an effective program to sustain.

For the sake of the socialist movement, NYC-DSA cannot afford to strike out alone under the coming Zohran administration. Every socialist in the country has a stake in what happens in New York. When we review the balance sheet of sewer socialism without obscuring the history out of political convenience, we know that we will not see victory in our lifetimes if socialism in twenty-first-century New York City goes the way of socialism in twentieth-century Milwaukee.

Bibliography

“Report of National Secretary to the Socialist Party National Convention, 1912,” May 1912, Duke University Archives and Manuscripts, Durham, North Carolina. Secretary Work reports a membership of 125,826 for the first quarter of 1912. This is around 10,000 higher than most figures that appear in the secondary literature.

Jeffrey A. Johnson, They Are All Red Out Here: Socialist Politics in the Pacific Northwest, 1895-1925 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), p. 107.

Report of Proceedings of the Thirty-Second Annual Convention of the American Federation of Labor (Washington, DC: The Law Reporter Printing Company, 1912), pp. 374-375; Report of Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth Annual Convention of the American Federation of Labor (Washington, DC: The Law Reporter Printing Company, 1915), pp. 443-444. Socialist labor organizer Max S. Hayes won a third of the vote in challenging Gompers for the presidency of the AFL in 1912; Socialist delegates won over forty percent of the vote on a motion to adopt a political campaign for the eight-hour day in 1914.

John HM Laslett, Labor and the Left: A Study of Socialist and Radical Influences in the American Labor Movement, 1881-1924 (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1970), pp. 98-99, 205, 216-217.

Victor L. Berger, “A Few Plain Pointers for Plain Working People—By a Plain Man,” essay, in Broadsides (Milwaukee, WI: Social-Democratic Publishing Co., 1912), 174-182, p. 178.

Berger, “How Will Socialism Come?,” Ibid, 25-30, pp. 27-8.

Berger, “Do We Want Progress by Catastrophe and Bloodshed or by Common Sense?,” Ibid, 228-235, pp. 231-233.

Ibid.

Joshua Kluever, “The Golden Age of Pragmatic Socialism: Wisconsin Socialists at the State Level, 1919-37,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 22 (2023): 204-223, p. 205.

Victor Berger, “The Misfortune of the Negroes,” Social Democratic Herald, May 31 1902. Accessed via Marxists Internet Archive.

Berger, “The Flag Superstition,” essay, in Broadsides, 97-103, p. 100.

David M. Chalmers, Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1987), p. 191.

Eugene V. Debs, “Unity and Victory,” speech addressing the Kansas American Federation of Labor, published in Labor & Freedom, 107–132. Accessed via Marxists Internet Archive. Here we have a notable example of Debs appealing directly to the membership of the AFL.

James Pruitt, “The Industrial Workers of the World: A West Coast Perspective,” Perspectives on Work 10, no. 2 (2007), 42-44.

Leo Troy, Trade Union Membership, 1897-1962 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1965), p. 2.

“The General Policy Statement And Labor Program of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers,” 1969, Box 1, Folder 86, American Left Ephemera Collection, University of Pittsburgh. Accessed via Marxists Internet Archive, p. 3.